Bridging the Nature Gap

Portland’s Riverton Trolley Park marks 125th anniversary with a conservancy’s commitment to its neighbors.

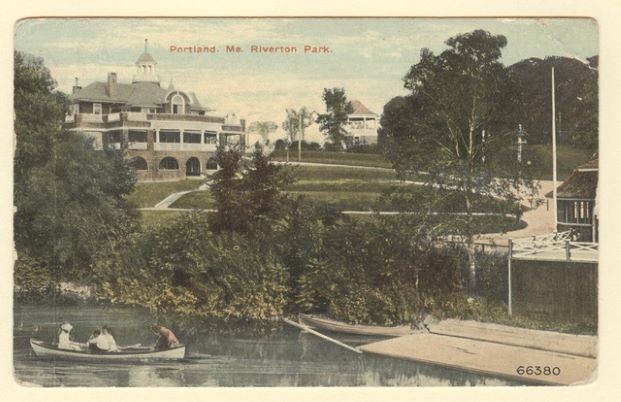

It’s hard to imagine, on an afternoon walk through Portland’s quiet Riverton Trolley Park, that some 10,000 visitors in long Victorian dresses, suits, and elaborate hats strolled the grounds for its opening day on June 27, 1896.

Today the park, with its tall trees and grassy paths, is silent save for a symphony of birds along the banks of the Presumpscot River. A few reminders of the park’s glorious past remain – large stone gates, scattered granite blocks, and a cascade of carved steps that lead to the water. Weathered copies of old images, tacked on posts along the path, show visitors what they might have seen so long ago.

Still, the future of Riverton Trolley Park remains hopeful despite its status as the city’s most underutilized public park. The Portland Parks Conservancy, with grants from MaineCF’s Conservation for All and Community Building grant programs, has embraced this historic gem as a place to welcome more Maine people to the outdoors.

Access for underserved communities and preserving the park’s history will play key roles in conservancy plans for its 20 acres. The Riverton neighborhood is one of Portland’s most racially diverse areas, home to many immigrants and refugees who live just a short walk from the park’s entrance behind a Little League ballfield.

While other parks in affluent neighborhoods have “friends of” groups that offer support, the effort to revitalize Riverton will rely primarily on grants and philanthropy. Nan Cumming, executive director of Portland Parks Conservancy, has high hopes a $500,000 federal matching grant, if approved, will provide the access and amenities that would draw neighborhood families and others.

Urban parks such as Riverton are essential to close the “nature gap,” where people have inequitable access to the outdoors based on race, income, and age. In Maine, 96 percent of low-income and non-white residents live in a nature-deprived area, according to 2017 U.S. Census statistics. MaineCF’s Conservation for All grant program aims to break down those barriers and help build strong connections between all Maine people and its land and water.

“One of the unique things about Maine is the proximity to special places all around us, whether that’s the local park, beach, stream, frog pond, or the 100-Mile Wilderness,” said Maggie Drummond-Bahl, senior program officer at MaineCF. “The hard truth is that access to these special places is not easy for all of us. This grant program aims to support organizations and programs that break down the barriers.”

This spring, the Conservation for All grant funded the Portland Parks Conservancy’s survey of neighbors – in seven languages. Nearly 400 people responded, including replies from people who don’t live in the area. The response, says Cumming, was gratifying, with real passion from neighbors and equal enthusiasm from folks who’d never even been to the park and saw potential for amenities that don’t exist elsewhere in the city.

At the top of the needs list are wayfinding and interpretive signs in several languages that would tell the site’s history and a kiosk to welcome visitors. The dream list includes a picnic pavilion, mountain bike/pump track, fields for pollinators, and community gardens.

The Community Building grant awarded this spring through MaineCF’s Cumberland County Fund will help fund a conservancy volunteer coordinator position. In July, the nonprofit organization also is launching the Portland Youth Corps, a leadership development and service program for young teens from disadvantaged backgrounds. Crew members will receive a stipend, mentoring, and work experience for conservation work in Portland parks.

“The whole public process has been personally very moving to me,” says Cumming. “The people I spoke with who live in the neighborhood truly do feel forgotten. They know what a huge impact the park will have on their lives and the future of their community.”

If you’d like to learn more about MaineCF’s Conservation for All grant program, please contact Maggie Drummond-Bahl at mbahl@mainecf.org.

A ca. 1910 postcard from the collection of the Seashore Trolley Museum, Kennebunkport, shows the park’s casino.

Riverton Trolley Park: Some History

The Portland Railroad Company built Riverton with hopes a 5-cent round-trip trolley ticket (including park admission) would draw working-class Portlanders from downtown to the edge of Westbrook on weekends when trolleys needed passengers.

Its lawns and flowers, envisioned by designers of the Boston Public Gardens, featured a large casino (not for gambling), dance hall, bandstand, carousel, small zoo, croquet field, and the outdoor Rustic Theater that could seat 2,500 people on a hillside amphitheater. Anglers would find a stocked trout pond or access to the Presumpscot River for canoes and small steamboats.

Parts of Riverton Trolley Park’s past still remain on the site, including steps that once led to a pavilion and the entrance gates. Photo at top: Jill Brady.